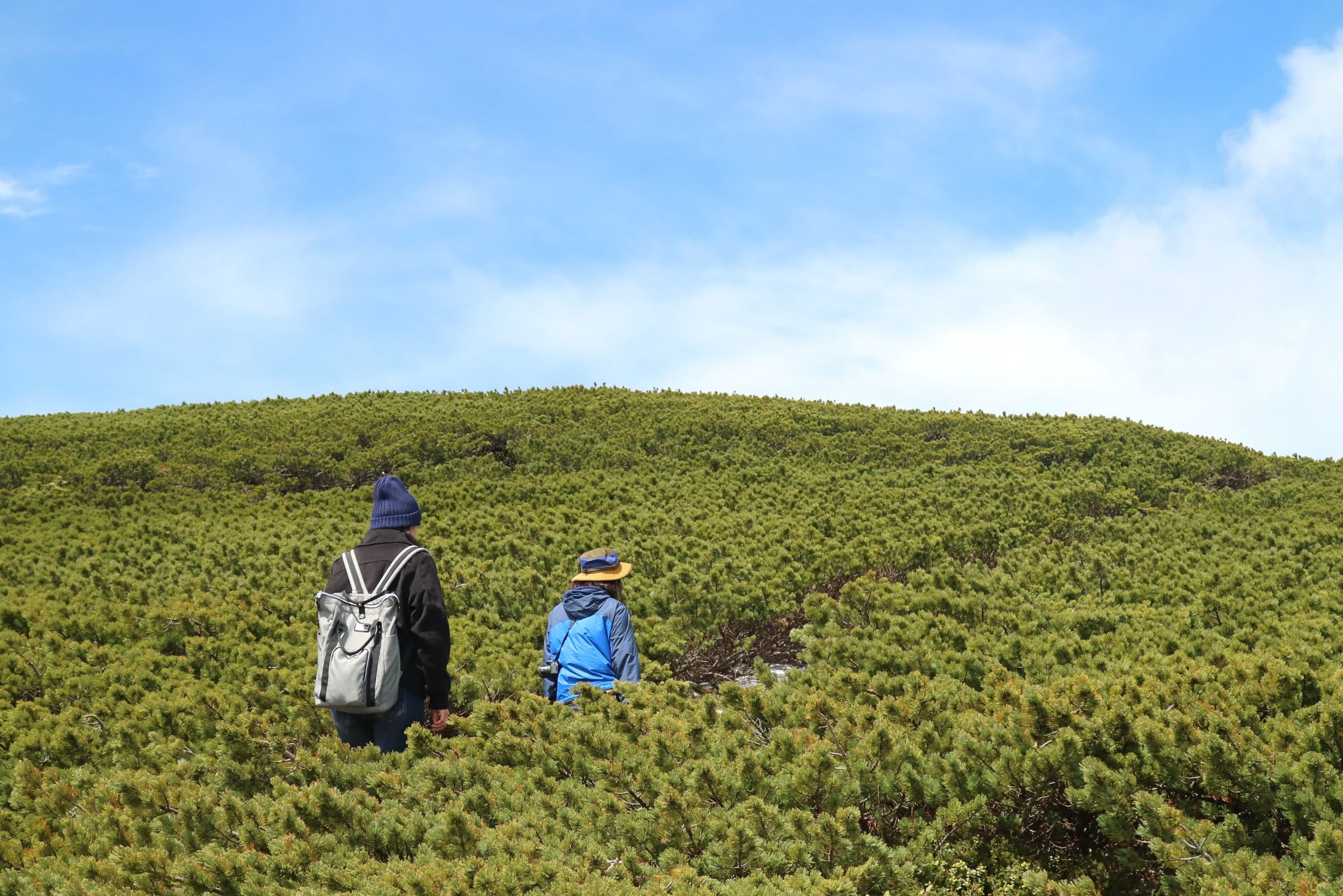

Norikura Skyline is the name given to the 14.4-kilometer paved road in Gifu Prefecture that connects Hirayu Pass (1,684 m) to Tatamidaira (2,702 m) near Mt. Norikura’s summit. Since 2003, private vehicle use has been banned on the Skyline to protect the natural environment; only buses, bicycles, taxis, and vehicles with special permits are allowed. The Nōhi Bus Company has been transporting passengers along the Skyline to the alpine peak since 1948.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the construction of such a high-altitude road must have seemed impossible, but in 1941 a project was started to do just that. The initiative was led by the Japanese Imperial Army, which had the financial resources and motivation to get the job done. With military tensions building in Asia and Japan’s entry into World War II on the horizon, the Army Aviation Headquarters initiated plans to build a high-altitude testing station for aircraft engines on the top of Mt. Norikura. Specifically, the military engineers sought to make fighter engines that could operate effectively at the same altitude as the American B-29 bombers (roughly 10,000 meters).

Construction on the road began in 1941. The army’s plan was to build the road 3 meters wide, just enough to accommodate military trucks. However, far-sighted local businessman Jojima Seiichi, the first president of Nōhi Bus Company, saw the road’s potential for postwar tourism. Jojima contributed ¥80,000 of his personal funds to the total construction budget of ¥420,000 (about ¥400 million today) to widen the planned road to 3.6 meters, which would eventually allow his buses to traverse it. By 1942, what had been a rough mountain trail just a year before had become a fully operational road, but in 1945 the war ended before it was ever put to military use.

In July 1948, the “Romance Car,” a ground-breaking vehicle with a glass roof, made its first commercial ascent of the road. Although the scenic views were superb, the Romance Car service ended after only a few years because the buses lacked a key feature: air-conditioning. The direct summer sun entering through the roof made the state-of-the-art vehicle feel more like a mobile sauna.

The Romance Car was canceled, but the bus service became a great success. Its popularity grew despite some inconveniences that might have unsettled modern passengers. For instance, the narrow switchback road was still unpaved and constantly blocked by newly fallen rocks, so the conductors had to disembark and remove them to proceed. When the buses arrived at particularly steep curves, passengers would be politely asked to get out and help push.

In 1955, Maud W. Makemson, a visiting astronomer from Vassar College, gave this account of her journey to Tatamidaira:

A string of buses moves briskly along a road hewn from the mountainside, hardly wide enough, it would seem, to avoid scraping the perpendicular wall on the one side or running off the unprotected edge on the other... At critical points, the girl-conductor stands on the rim of the road voicing encouragement to the driver in a high, singsong falsetto: “Ar-ri-i-e-e-e! Ar-ri-i-e-e-e!” until the danger is safely passed. The American word “all right” has found its way into the very heart of the Japanese language.

Records show that in 1959, 116,000 passengers used the service over 56 days of operation. With the increase in private car ownership in the 1960s, these figures fell, but the Nōhi buses remained in operation. In 1973, the road—paved with asphalt and much improved since its earlier days—was officially named the Norikura Skyline. In 2003, private motor vehicles were restricted to reduce traffic and protect Mt. Norikura’s natural environment. Consequently, Nōhi buses continue to be the principal means of traveling the Norikura Skyline.

![]()